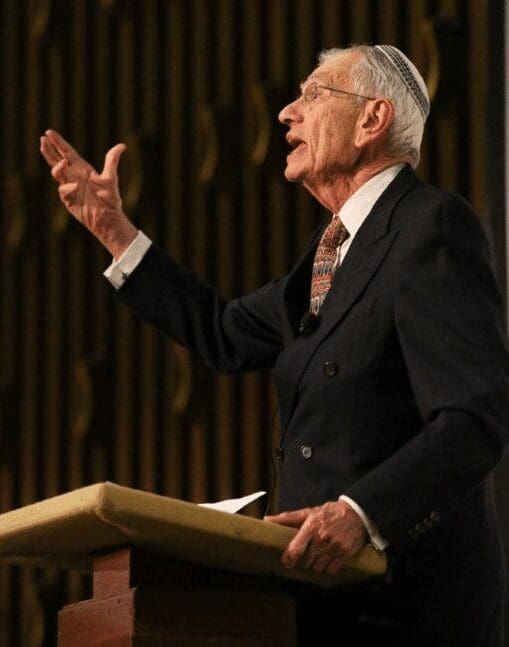

Torah Commentary with Rabbi Laurence Rosenthal

Parshat Trumah

Exodus 25:1 - 27:19; Haftara: I Kings 5:26 - 6:13

By Rabbi Laurence Rosenthal

This week's Torah begins with a different sort of mitzvah, or commandment. In readings prior to and following Parshat Trumah, commandments are stated without an "opt in" or "opt out" clause; we are commanded by a long list of "thou shalt and thou shalt not" pronouncements, and there is no discussion. According to our tradition, these are the orders of God and they are to be obeyed. However, this week's sidra begins a little differently. It states:

דַּבֵּר אֶל־בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וְיִקְחוּ־לִי תְּרוּמָה מֵאֵת כָּל־אִישׁ אֲשֶׁר יִדְּבֶנּוּ לִבּוֹ תִּקְחוּ אֶת־תְּרוּמָתִי:

Speak to the Children of Israel and take for Me gifts from any person whose heart is willing, take My (me?) gifts.

Our Torah portion shares the beginning of a capital campaign, inviting the recently freed Jews, wandering through the wilderness, to offer specific donations which will be used to erect the tabernacle and the tent of meeting which provide a place for God's presence to dwell amongst the people. Unlike other commandments, this one needed to be fulfilled willingly, with a gracious heart. Presumably, if one's heart wasn't willing, one wouldn't need to give. There doesn't appear to be a consequence for not giving. As a building project goes, this is a risky endeavor. What would have happened if enough wasn't collected? What if the people's hearts weren't so open and giving? After all, we have already heard the grumbling of the people on this expedition. Based on the complaining that the Israelites have voiced so far, I wouldn't have imagined that they would be so quick to pull out their checkbooks. However, in the end, we know that the people gave willingly and generously, even requiring Moses to put a halt to the collection due to excess. As a congregational Rabbi, I would love to experience that problem!

Apparently, the commandment to collect gifts for this project wasn't really about a capital or building campaign. In fact, to this point, we know very little about what was to be built. The people were simply told to give generously, according to their hearts' desire – and they did. Giving is a spiritual exercise that is for more than just helping others or creating good feeling. There is something important that happens to the person giving, which can't happen unless they give. The reasoning seems somewhat circular: we must give according to our giving nature, but that giving nature is created by the act of giving. Rabbi Nachman of Breslov gives an important insight into the purpose of this spiritual exercise.

ליקוטי מוהר"ן, תנינא ע״א:ז׳:א׳

וְנֹעַם הָעֶלְיוֹן שׁוֹפֵעַ תָּמִיד, אֲבָל צְרִיכִין כְּלִי לְקַבֵּל עַל־יָדוֹ שֶׁפַע נֹעַם הָעֶלְיוֹן. וְדַע, שֶׁעַל־יְדֵי צְדָקָה נַעֲשֶׂה הַכְּלִי לְקַבֵּל עַל־יָדָהּ מִנֹּעַם הָעֶלְיוֹן שַׁלְהוֹבִין דִּרְחִימוּתָא, כִּי צְדָקָה הִיא נְדִיבוּת לֵב, כְּמוֹ שֶׁכָּתוּב (שמות כ״ה:ב׳): מֵאֵת כָּל אִישׁ אֲשֶׁר יִדְּבֶנוּ לִבּוֹ תִּקְחוּ אֶת תְּרוּמָתִי; וּנְדִיבוּת לֵב, הַיְנוּ שֶׁנִּפְתָּח וְנִתְנַדֵּב הַלֵּב, וְעַל־יְדֵי־זֶה נִפְתָּחִין שְׁבִילִין דְּלִבָּא, וְנַעֲשִׂין כְּלִי לְקַבֵּל שַׁלְהוֹבִין דִּרְחִימוּתָא, שֶׁנִּמְשָׁכִין מִנֹּעַם הָעֶלְיוֹן כַּנַּ"ל.

Likutei Moharan, Part II 71:7:1

Now, goodness from on high flows continuously. Nevertheless, one must have a vessel with which to receive the influx of this supernal goodness. And know! the vessel with which to receive flames of love from this heavenly goodness which flows into the world is forged through charity. For charity is the generosity of the heart, as it is written (Exodus 25:2), "from every person, as his heart urges him, you shall take My donation." Generosity is that the heart is open and benevolent. As a result, the pathways of the heart open and become a vessel for receiving the flames of love drawn from Supernal goodness, as mentioned above.

The tzedakah we give offers more than resources for others and a good feeling to ourselves. Cultivating and nurturing a giving heart transforms us into vessels that will enable the goodness of God to be contained therein, and travel through the world.